TEDx Melbourne The Year of Living Virtually

"A digital tool set makes possible a story that is adaptive not static. Potentially much more like memory and more like us... Which is a really interesting proposition for education, learning environments and shared creativity."

On August 3rd 2016, I spoke at TEDx Melbourne about how digital narrative, a small corner of the storytelling universe, is changing the fundamental format of Story. I'd been invited to talk two years previously and this was a chance to eventually say ‘yes, ok!’

TBH, given the opportunity in the future, I'd love to try again! Below's a transcript of the talk, worth a read if you’re interested in storytelling at all.

<shudders>and if you scroll down, you can also watch!</shudders>

I’m going to talk today about how a small corner of the storytelling universe is changing and how this change is truly great for education.

I’m a writer and visual artist, I’m not specifically an educator, but I have been involved for years in different types of digital narrative: writing and designing story worlds, showing other storytellers and program makers how their work can be enhanced, expanded in the digital space, and also facilitating access to other people’s stories.

One thread through all of this has been how over the years, the digital revolution has been supplying storytellers with an increasingly amazing tool set.

Stories are essentially a form of memory. They have this unspoken, fundamental importance in our lives because as social creatures, sharing memories in entertaining and instructive ways fulfills fundamental drives in us.

Actually, here we are at TED, a hugely social facility for ideas and storytelling, and which relates very specifically to the idea I want to share.

You see, whilst I was trying to make this talk (I want to say good but let’s go with concise), I went and watched one of TED’s most seminal talks, which is ten years old now, given by Sir Ken Robinson. Only has 40 million plus views, so no big deal.

It’s a great talk, but the thing about it was there were three hooks in it that really tied things up for me. And I thought, yes, my talk is about answering the call of another TED Talk’s’ challenges. Challenges that after 10 years are still very much out there.

There are three pretty provocative observations made by Sir Ken:

Creativity is as important as literacy in education;

We tend to get get educated out of creativity;

Ideas of value, more often than not come about through an interaction between different disciplinary ways of seeing.

The new craft of digital narrative can respond to these challenges brilliantly, because it provides a state for creative learning that is adaptable, fluid, dynamic and social. Like us.

I want to touch on two types of this storytelling today.

Before we get to them, I’ve got a metaphor in two parts to share and hopefully it helps in explaining how a digital approach really brings something new to the fundamental form of a story. It’s got a bit of philosophy of mind and it’s got a bit of Oscar Wilde. And it starts with a question: why is narrative, in its manifold forms, so foundational to the human experience anyway?

Well, perhaps because our ability for self-reflection combines with the biological drive to be social, leading us to re-imagine memories and experiences in entertaining and instructive ways – in other words, generate and consume stories together and seemingly as soon as we can.

Let me just read to you what two academics, Roger Schank, Robert Abelson have said about this: “The reason that humans constantly relate stories to each other is that stories is all they have to relate. Put another way, when it comes to interaction in language, all of our knowledge is contained in stories and the mechanisms to construct them and retrieve them.”

Stories are forms of memories which we share with each other and also format into media: books, cinema, television, you name it. Narrative is a fundamental aspect to the experience of our lives and how we learn about it. And it’s developed out of our earliest forms of communication.

So let’s retreat to the bright corner of the storytelling universe that I’m talking about, and ask what if narrative was formatted to be more like us? Not static, but adaptive, dynamic and social?

You could say this is already happening, with information, in the way we consume it daily – it’s dynamic and social.

But what about at the deeper level of storytelling, and where this time you can have an influence on the nature of the story in a way that encourages creativity and interaction between different disciplinary ways of seeing. This would be amazing as a learning environment.

Now I want to add in Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray.

Oscar Wilde’s famous story is about a fortunate young man influenced to pursue a narcissistic life of hedonism and aesthetics, just as an extraordinary portrait of him is being completed. When it’s finished, Dorian keeps the painting of himself out of sight, in the attic and lives large.

Over time, he notices that the portrait changes to reflect the morally corrupt actions he commits in real life. And all the while he continues to resemble his unscathed self in the portrait when it was painted. So spoiler alert – it ends badly!

But, it’s the use of the ‘magical portrait’ that we’re interested in here. The digital narrative toolset enables a story device, in this case a portrait that can magically reflect Dorian’s moral self, in completely new ways.

So, a minute amount of audience participation – which is a bit rich coming from someone who dreads audience participation! But it’s pretty low-key.

Bring to mind a picture you’re really familiar with, maybe one that’s been in your life for some time.

Maybe you’ve looked at that picture and caught yourself thinking – something’s different this time.

For sure, the picture is exactly the same, because it’s you who’s changed since you last saw it. Your experiences that make that picture seem different.

Bring to mind a book or a film in the same way. When you read or watch it again years later it might feel different because your memories and your experiences in the world have made you different.

What’s new about digital storytelling is that it allows the picture or story itself to change, not just your perception of it.

A digital tool set makes possible a story that is adaptive not static. Potentially much more like memory and more like us.

Which is a really interesting proposition for education, learning environments and shared creativity.

Digital has touched many of the existing forms of story in amazing ways. Books are not just in print anymore, radio and television have decoupled from appointment listening and viewing and cinema has evolved as a medium to have a longer life span across many different screens.

The first of the new story types I’m talking about is still emerging.

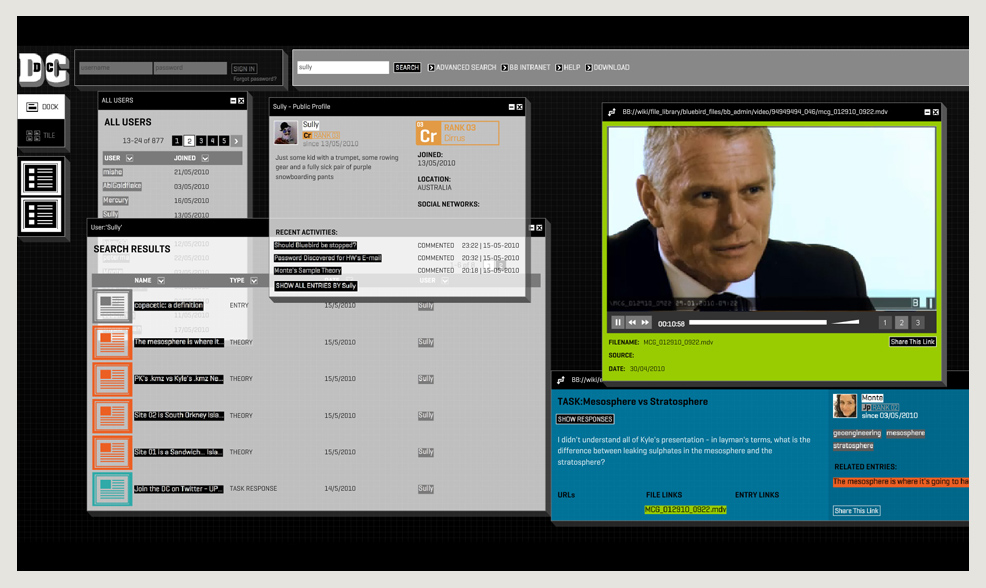

About five years ago, I worked on Bluebird AR. The AR stood for Alternate Reality.

It was a story in which the audience were a crucial part of the outcome – the story was what came out of the collision between storytellers and audience.

Bluebird is an example of what happens when the photograph or narrative, as in the metaphor, is changed when it’s looked at.

Bluebird was played out online across websites, social media and a central social hub in which the audience worked together to unravel plot, control the pacing and to some extent the direction of the story.

And it responded to Sir Ken’s observations perfectly.

It put maximum emphasis on creative problem solving and interaction between different disciplinary ways of seeing, and rewarded it with authorship in progressing the story.

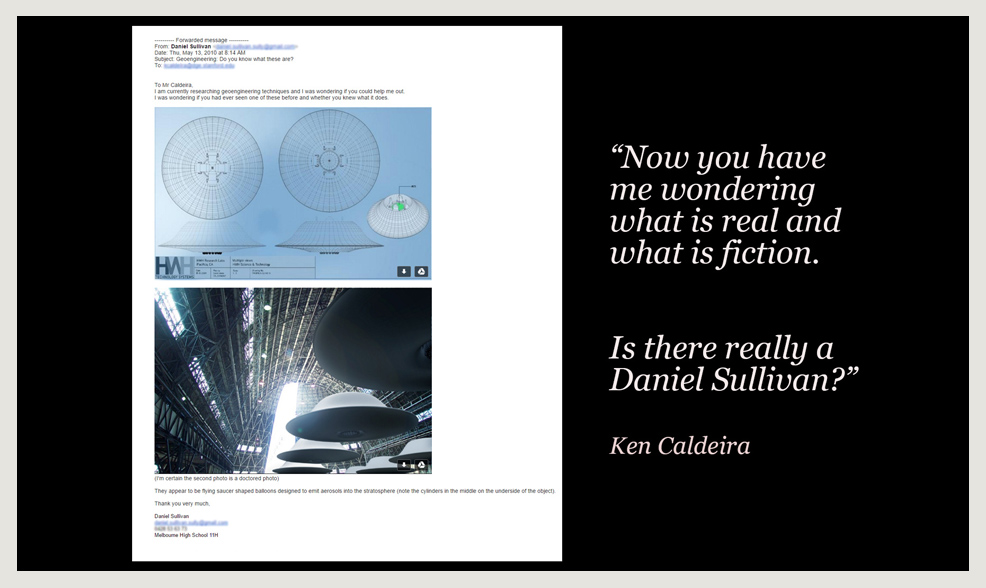

One day whilst Bluebird was in full swing, we received an email from a leading climate scientist at Carnegie Institute for Science, who had been one of our advisors during pre-production.

He was forwarding an email he’d received from a Year 11 student of Melbourne High School.

As this student researched and built theories in the world of Bluebird, he was asking a real-world leading expert in geoengineering if he knew what the images were of and whether they had the potential to be viable geoengineering solutions.

Sully, as the student was known in the game world, was one of Bluebird’s star players.

I think the lessons of Bluebird are more relevant than ever, not for entertainment but for education.

I think they articulate a highly creative approach to learning, especially complex ideas and the interaction between different disciplinary ways of seeing and in a learning environment that is dynamic and social and, perhaps most importantly digitally native.

So the second type of digital narrative I want to introduce today is the important flip side to the Bluebird model, in which the stories of the past can be revisited and expressed in this new language.

We’ve called this factual multimedia for some time, meaning that you can bring previously separate, often ephemeral items of media together to tell a more complete story of actual events.

I’ve been incredibly fortunate to revisit the story of the Sydney Opera House on two occasions in recent years.

The thing about Sydney Opera House is that the story of the building and how it came about articulates why it is such an incredible place – your appreciation of the monumental effort that went into its creation massively enhances your understanding of the place, but also much broader ideas and lessons in humanity, creativity, Australian social and political history, architecture, modernism, for example.

You begin to understand that its significance as a performance venue and world heritage listed masterpiece, is informed by an incredible backstory. You’re informed view is now contextualised, more complete, more 360 in perspective.

What the craft of digital narrative is doing here is taking the multiple threads of storytelling and binding them into a meta-story device that gives you the audience a deeper, contextual understanding.

So here’s an example. Here, we’re taking a look at one aspect of the story, the important discovery of the theory for the roof of Sydney Opera House, the Spherical Solution.

This is of course a fundamental element of the building – why is Sydney Opera House so recognisable? Because of the profile of the shells.

In this one chapter of the story, resides the context for understanding the principal, its back story, and its enduring significance. And this content exists in a variety of forms from archival photographs and film to newly created animations of the principle, to writing and interviews. All brought together.

A few of weeks ago I finished working on an app that revisits the little known battles of Fromelles and Pozières in this same meta-story context.

The events of the battle are recorded at the time and place where they occurred, whilst a chaptered story leads you through the central narrative. The depth of detail drawn from the experience is completely up to you, from watching the story of the battle, through to understanding the machinery of war, the diaries and profiles of soldiers, and modern day analysis. All in one app on one device.

Why I think these new models fit so well with education is that the audience behaviour is active rather than passive. It involves reaching into the experience.

You have, to varying degrees, to work with the narrative in order to be part of the story. You learn through the experience of participating. Just like life.

This year is marked by another jump for digital narrative, into virtuality.

It’s early days for Virtual Reality. Even though the ideas and versions of the tech have been with us for decades.

But its emergence this year as a consumer device is a hugely significant moment in this digital revolution. And why, although I’ve been talking about stories, I chose the title of this talk to reflect this new wave.

We may see it as a novelty now, but the principle and potential that VR points to is likely to become a more significant shift in perception than was seeing the earth from space. It may push human experiences forward in incredible ways.

VR promises to be a great evolution for some of the ideas I’ve been talking about for the past few minutes.

Thanks for [reading].